Rapists know your limits

There's a poster produced by the UK government recently that says:

1 in 3 rape victims have been drinking. Know your limits.

I can imagine there are people in a design agency somewhere trying to think up stark messages to make the nation collectively put down its can of Tennents for at least a moment, and it's good to dissuade people from problem drinking. But this is probably the most blatant example I've ever seen of what people have been calling "victim blaming".

If your friend came to you and said they'd been raped, would you say "You shouldn't have been drinking"? I hope not. And not just because it'd be rude! But because even when someone is a bit tipsy, it's not their fault they were raped, it's the rapist's fault.

It sounds so pathetically obvious when you write it down like that. But clearly it still needs to be said, because there are people putting together posters that totally miss the point. They should also bear in mind that a lot of people like to have a drink on a night out, or on a night in. (More than half of women in the UK drink one or two times a week, according to the 2010 General Lifestyle Survey table 2.5c) So it's actually no surprise AT ALL that 1/3 of rape victims have been drinking. What proportion of rape victims have been smoking? Dancing? Texting?

(By the way there's currently a petition against the advert.)

On the other hand, maybe it's worth thinking about the other side of the coin. People who end up as convicted rapists - some of them after a fuzzy night out or whatever - how many of them have been drinking? Does that matter? Yes, it matters more, because rape is an act of commission, and it seems likely that in some proportion of rapes a person went beyond reasonable bounds as a result of their drinking.

So how about this for a poster slogan:

1 in 3 rapists have been drinking. Know your limits.

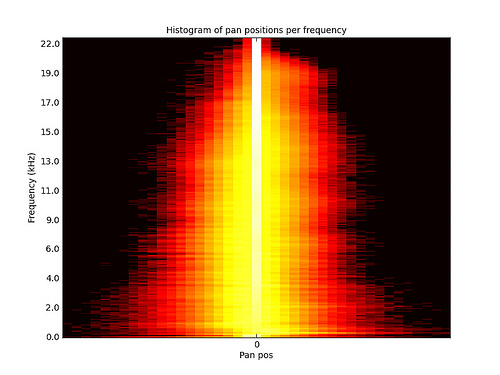

(I can't find an exact statistic to pin down the number precisely - here I found an ONS graph which tells us in around 40% of violent crimes, the offender appears to have been drinking. So for rape specifically I don't know, but 1 in 3 is probably not wide of the mark.)

So now here's a question: why didn't they end up with that as a slogan? Is it because they were specifically tasked with cutting down women's drinking for some reason, and just came up with a bad idea? Or is it because victim-blaming for rape just sits there at a low level in our culture, in the backs of our minds, in the way we frame these issues?

Syndicated 2014-07-23 03:20:54 (Updated 2014-07-23 03:22:58) from Dan Stowell